2025: New Ventures Exhibition

Our history2025: New Ventures Exhibition

From 1976 to the opening of 2025’s The Nest, CFT has experimented with temporary performance spaces providing freedom and opportunity to emerging artists and new experiences to Chichester audiences.

We unearthed the hidden history of these theatrical moments and spaces with the help of a super team of volunteers. And following a touring exhibition, this page is here to share the history of our temporary spaces. Resonating in all the stories shared are experiences of opportunity and hard work, as well as an energising shared purpose to try something new, take risks, and of course revel in the joy of theatre!

Our Volunteers

Using money raised by National Lottery players, The National Lottery Heritage Fund supports projects that connect people and communities with the UK’s heritage.

New Ventures Exhibition is made possible with The National Lottery Heritage Fund. Thanks to National Lottery players, and the help of a super team of volunteers: Phil Ayling, Gilli Bush-Bailey, Chiara Bradfield, Andy Earwaker, Rachel Green, Kay Gilmore, Bob Harvey, Martin Reynolds, Mary Tennant, Andrew Vance and Stavroula Varella for their amazing research.

CFT’s Volunteering Programme is kindly supported by Prof. E. F. Juniper and Mrs Jilly Styles. With thanks also to work experience students, Josh Brooke and Pidge Thorner, who joined us from the University of Chichester.

Through the decades

Early days

When Keith Michell became Artistic Director in 1974, Chichester Festival Theatre began to shake off its formal past.

Out went the playing of the National Anthem before shows; in came handwritten notes from Michell in every staff programme. First names replaced job titles, and a new, spirited atmosphere took hold. A younger, more diverse company arrived. After his breakout in Follow the Star, a young Tony Robinson returned for leading roles and joined forces with fellow actors to form a bold new fringe group. He became Production Associate, helping drive a fresh wave of creativity. The repertory model – where actors stayed for a full season – gave space for risk and invention.

New Ventures, a grassroots off shoot, brought theatre into schools, prisons and unexpected corners of Chichester. Funded by community darts matches, jumble sales and local generosity, New Ventures proved that powerful, meaningful theatre didn’t need a grand stage – just imagination and heart.

New Ventures began quietly – with Saturday morning storytelling in the CFT foyer and Chichester Library – but it didn’t stay quiet for long.

Story cassettes were recorded for hospitals and housebound residents, spreading the joy of theatre to those who couldn’t come to the stage. Performances popped up all over town. The grand dining room of the Dolphin and Anchor Hotel became a makeshift theatre, with a central stage that resembled a boxing ring. Parking was tricky – some audience members walked out mid-show to avoid getting towed! In 1977, The Battle of Britain, created with local stories from ex-pilots in Tangmere and directed by Tony Robinson, brought music and memories together in a community-led production. By 1979, New Park Community Centre became home base. With DIY seating blocks and a mobile stage, New Ventures kept its performances lively, inventive, and truly local.

Murder in the Cathedral

George Bell, Bishop of Chichester from 1929 to 1958, commissioned Murder in the Cathedral from poet T.S. Eliot in 1935, believing that drama could deepen spiritual understanding.

The play, which tells the story of Thomas Becket’s (the Archbishop of Canterbury) martyrdom, was first performed in Canterbury Cathedral, marking a powerful fusion of art and sacred space. Bell’s vision for connecting the Church with contemporary culture helped inspire future ecclesiastical performances. 2025 marks the 48th anniversary of CFT’s production of Murder in the Cathedral, which was performed within Chichester Cathedral itself, bringing George Bell’s ideas full circle. It was undoubtedly the most ambitious production up to this point. It was the climax of the New Ventures 1977 season, and featured an A-list cast of actors.

Utilising the expertise of CFT’s technical team, this production rivalled anything that had been produced on the CFT stage. Chichester Cathedral was the third main venue used by New Ventures, which hosted the season finales in both September 1977 and 1978. However, the Cathedral proved to be a challenging venue, largely due to difficult acoustics and limited lighting capabilities.

CFT Associate Director, Anthony Chardet invited the international drinks company Martini to see a performance of Murder in the Cathedral, and they were so impressed that they became the major sponsor of Chichester Festival Theatre for eight years, and were CFT’s first commercial sponsor.

Later, in 1986, as part of The Tent’s programming, was a production of The Spershott Version. This promenade performance roamed the city centre with scenes taking place in Bishop’s Palace Gardens, continuing the fringe theatre collaboration between CFT and Chichester Cathedral.

And this venture blossomed. Until today, the vision of it had been that like poppies in a field. It blossomed and then disappeared. To know how influential it was, is really quite emotional.

Sir Tony Robinson

1980's

The Studio Company

When Patrick Garland became Artistic Director in 1981, he brought with him a fresh sense of purpose.

One of his first bold steps was to reimagine the fringe New Ventures group, giving it a sharper identity as the Chichester Festival Theatre Studio Company. At the season launch, Garland quipped: ‘We’ve changed the name from New Ventures – it had a schoolmasterly, outward-bound ring about it!’ His goal was clear: to carve out a space for more daring, contemporary theatre that could sit alongside – but not beneath – the Main House. The Studio Company drew from the Festival’s acting ensemble and was awarded £2,000 to stage new writing, late-night experiments, and children’s shows. Garland didn’t just want theatre in Chichester – he wanted it everywhere, for everyone. His leadership helped elevate small-scale productions with big ideas, championing innovation and inclusivity during a pivotal moment in the theatre’s history.

The CFT Studio Company packed a punch with its eclectic 1981–1982 seasons.

Performing at the modest New Park Community Centre, the company made a virtue of its limitations, turning a shared community space into a stage for experimentation and storytelling.

The New Park Community Centre became a particularly vibrant discovery in the research conducted by volunteers. Their personal memories of the Centre, deeply embedded in Chichester’s civic life, uncovered its use by New Ventures and the fact that it was saved from demolition thanks to a donation from the New Ventures Company. This stands out as a vivid example of (re)discovering community memory.

Productions included full length plays, children’s theatre, and 30-minute late night performances like Skinny Spew and Gum and Goo – a wild, surreal rollercoaster that left audiences equal parts baffled and delighted. It’s review in the Bognor Regis Observer ends with ‘Words could never capture this offbeat, crazy piece of nonsense with its disturbed overtones and manic traits. It was an excursion into the minds of two persona non grata, thankfully played largely, for laughs, but were people really willing to pay £1 a head to see just 30-minutes of bizarre drama?’

A young writer, John Mash, offered a quirky cricket-themed debut with his play Howzat, while his second play, Modigliani, proved a dark and compelling exploration of the artist’s final years. Both were directed by Christopher Selbie and earned strong reviews. These productions were a platform for new voices and fresh approaches. Affordable tickets (from 50p to £1.50), inventive staging, and daring choices helped The Studio Company establish itself as a vital and dynamic part of the Festival.

More than just performances, the Studio Company’s mission was to make great theatre and share it with the community.

In 1981, workshops were held in schools across Lavant, Petworth and Chichester, led by actors and Assistant Director of the Studio Company, Christopher Selbie. Students explored Shakespeare, rehearsed scenes, and even joined a vibrant, promenade style performance of The Canterbury Tales that wove through city streets and ended at the Cathedral Green. According to the report on The Studio Company’s 1981 season by Angers Pope, the company broke even. Chris Selbie thought that the profit margin could be higher if publicity had been better. But the problem was that nobody really knew whose responsibility the publicity for The Studio was.

The Tent

The Tent arrives – 1983

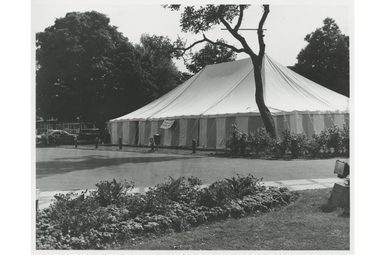

‘What was born in a hotel, went to school, and now lives in a tent...’

So began a cheeky 1983 CFT press release. The punchline... Chichester’s much-loved fringe theatre space. That year, under Executive Producer John Gale, a bold move gave the experimental Studio Company a seasonal home – a yellow-and-white striped marquee, bought for £4,000 with help from loyal supporter Henny Gestetner. Erected beside the main house, The Tent brought unconventional theatre right to CFT’s doorstep, with The Tent Artistic Director Matthew Francis at the helm. It buzzed with lunchtime plays, late-night shows and new writing. Performers embraced its quirks – and its leaks. Rainy nights meant broom handles at the ready to stop water pooling on the roof. But none of that dampened The Tent’s spirit.

New voices, new audiences

The Tent quickly became a launchpad for fresh talent and fearless storytelling. In its debut year, 17-year-old Edward Kemp’s The Iron and the Oak – written at just 15 – won a new writing competition and was staged in The Tent. More followed: youth-led pieces, political gigs, and wild experiments. In 1984, Shades of Grey cast Youth Theatre members alongside just one adult – Jason Carter as a wounded German pilot. It was bold, local and unforgettable. One year later, Chichester Festival Youth Theatre (CFYT) was officially born. Inside The Tent, roles were fluid. Assistant stage managers became directors. Technicians turned actors.

‘Throw it all together and just do it,’recalled Caroline Sharman-Mendoza. The Tent was a space where anyone with a spark could make something happen. From wartime memories in The Spershott Version – featuring horses, fi reworks and over 100 locals – to sand-filled stages in Salonika, The Tent was Chichester’s creative playground.

Farewell to the fringe: The Tent’s legacy, 1983–1988

By the mid-1980s, The Tent had carved out its own identity. It wasn’t just an overflow space – it was a destination for risk, humour and heart. Musicians like Billy Bragg were invited to ‘sing his excellent and radical songs in this conservative heartland.’ The Bash’s Backstage Boogie Band closed the 1985 season with a celebration led by CFT’s backstage and front of house crews.

In its final years, The Tent also navigated the tensions of professional theatre. Early productions were mostly non-Equity, giving emerging performers a foot in the door – even as debates over fair pay and access simmered. In 1988, Sam Mendes directed Translations by Brian Friel – a thoughtful, powerful piece about language and identity. It marked a maturing moment for the space, just as The Tent prepared to bow out. By its last season, The Tent was affectionately known as the ‘Minerva Tent,’ a stepping stone to the Minerva Theatre’s opening. When the canvas came down for the final time, one member of the tech team tore a piece of fabric to keep – a small, sandy, muddy scrap of theatre magic.

We are trying to provide a professional, artistic alternative to the work done in the main theatre.

Christopher Selbie, Artistic Director of the CFT Studio Company

We do want to reach an audience that would not attend the main house – especially young people.

Christopher Selbie, Artistic Director of the CFT Studio Company

A steamy marquee on a hot summer evening...thunder rolling in the background... it had its discomforts, but also a kind of poetry.

Director Sam Mendes

Fast Forward to 2012

Theatre on the Fly

To mark Chichester Festival Theatre’s 50th anniversary in 2012, Artistic and Executive Directors Jonathan Church and Alan Finch revived the spirit of The Tent with a bold new temporary space: Theatre on the Fly.

Rather than recreate the past, they envisioned a venue that would speak to the needs of a new generation. They commissioned Assemble, an emerging design collective known for grassroots architecture. Inspired by the mechanics of a traditional fly tower – something neither CFT nor Minerva had – Assemble created a raw, rainproof structure that responded to the landscape and invited open engagement. Built with help from volunteers, Theatre on the Fly was both a physical space and a statement of intent.

A platform for new voices

The season featured three productions, each directed by an emerging director from CFT’s training programme: Anna Ledwich, Michael Oakley and Tim Hoare. Denis Potter’s Blue Remembered Hills opened the season, using Oaklands Park itself as a living set. Playhouse Creatures made inventive use of the new fly system, marking the start of an ongoing collaboration with playwright April De Angelis. The Youth Theatre staged Noah, transforming the park into a surreal procession of animals and flood survivors. Fred’s Diner, a world premiere by Penelope Skinner, closed the season – its roadside setting echoed by the hum of traffic on the nearby A286.

The Process

Built by the community, carried forward by youth

Assemble’s process echoed The Tent’s community roots – local volunteers, Youth Theatre members and theatre supporters all helped build Theatre on the Fly. Roles like the ‘High Flyer’ gave older Youth Theatre members the chance to work alongside professionals, sometimes even stepping into rehearsals. Sustainable choices – repurposed seating from Oldham Coliseum, wood from the Finborough Theatre, and a post-season donation of scaffolding boards to Aldingbourne Trust – reflected a broader sense of purpose. Though temporary in form, the space left a lasting impact on participants’ skills, careers and connection to theatre-making.

There was a sort of organised chaos to the thing. It always felt like it was teetering on the brink of impossibility. But I think also that was part of the spirit too, the notion of an impossible theatre seems to be within the lineage of Chichester’s history. What’s really wonderful about temporary theatre space is that it immediately demands the audience have a different relationship to the to the piece.

Anna Ledwich, Theatre on the Fly, Apprentice Director

2013

Theatre in the Park

The summer we ran away to the circus

A different kind of temporary space.

Unlike The Tent or Theatre on the Fly, Theatre in the Park wasn’t created for experimentation or grassroots innovation – but to preserve the continuity of Chichester Festival Theatre’s summer season during major redevelopment. While the Festival Theatre underwent a £22 million renovation, CFT was determined that 2013 would not be a lost season.

Audiences, artists and staff were at the heart of this ambitious project, which aimed to retain both community connection and a skilled workforce. Theatre in the Park was designed to echo the experience of the Festival Theatre: it seated 1,200 people and recreated the familiar intimacy, acoustics and atmosphere of the main house. The 52-metre-wide tent structure, manufactured by French company VSO, was completed in just four weeks.

It was equipped to full professional standards, including theatre-grade lighting and sound, air conditioning and accessible amenities. A new path was built across Oaklands Park to improve access, and golf buggies ferried patrons with access needs directly to the door. Festoon lights lit the way across the grass and former Technical Director Sam Garner-Gibbons recalled riding his bike across the park after evening shows, switching off the lights one by one.

Staging Spectacle

Two productions were staged that summer, each using the space’s scale and character to full effect. Barnum, produced in association with Cameron Mackintosh, opened the season.

This revised version of Cy Coleman and Michael Stewart’s musical, adapted by Mackintosh and Mark Bramble, embraced the circus-like nature of the tent. Audiences were swept up in the show’s energy and spectacle, blurring the line between theatre and big top. The second production, Neville’s Island by Tim Firth, brought a different kind of immersion. First commissioned by Alan Ayckbourn in 1992, the play follows four men stranded on a Cumbrian lake during a team-building exercise. The production made use of the tent’s flexible design to incorporate water, soil, and naturalistic elements, heightening the visceral realism of the performance.

A temporary home with lasting impact

The 2013 season was more than a logistical solution – it was a rejuvenating chapter for CFT. For many staff, it felt like a summer adventure. Theatre in the Park demonstrated how a temporary space could hold a sense of permanence – of belonging – even when built to disappear.

It was the summer we ran away to the circus.

Loz Tait and Helen Flower, Costume team

‘The temporary theatre was not just a stopgap; it was a testament to our resilience.

Alan Finch, CFT Executive Director (2005–2016)

2019

The Spiegeltent

In October 2019, a striking new structure appeared in Oaklands Park: The Spiegeltent. It was the fourth temporary venue to be installed by Chichester Festival Theatre, following The Tent (1980s), Theatre on the Fly (2012) and Theatre in the Park (2013).

Like its predecessors, The Spiegeltent had a distinct purpose – to test the potential of a third venue for programming and to reach new, more diverse audiences. At the heart of the project was a bold production: Roy Williams’ Sing Yer Heart Out for the Lads, an immersive, politically charged play set in a South London pub during the infamous 2000 England vs Germany football match. The play had originally premiered in the National Theatre’s temporary venue, The Loft, in 2002. A local pub was considered early in planning, but this proved impractical for a full run. Then came the idea of a Spiegeltent.

A mirror tent with a touring spirit

The term Spiegeltent comes from the Dutch word for “mirror” – a nod to the mirrored interior of these distinctive European performance tents. The first was built in Belgium in 1910 by mirror designer Oscar Mols Dom and tent maker Louis Goor. Designed to be taken apart and rebuilt at each destination, Spiegeltents have since become a feature at festivals and fringe events around the world. The tent that arrived in Chichester was hired from Magic Mirrors. Made up of some 3,000 pieces of wood, canvas, mirrors, and stained glass, it was constructed entirely without bolts or nails. Once assembled, it became The King George pub for the season – a name taken from the fictional setting of Williams’ play. To complete the illusion, a pub sign and boards decorated the outside, a real bar, pool table and darts board inside and a police car with flashing blue lights was stationed outside the venue.

Beyond the Pub

In addition to the main production, The Spiegeltent hosted a season of late-night cabarets and special events, with signage hand-painted by CFT staff and posters designed in-house. Staff even helped build a temporary outdoor bar for audiences in the space normally used by performers and crew in the Green Room garden. The atmosphere was festive, but true to

type, Chichester audiences waited politely for a pause in the performance before ordering drinks at the bar. These experiments led directly to the creation of CFT Lates, a popular series of late-night events.

A lasting impact

The Spiegeltent successfully reached new audiences and demonstrated the value of a flexible, third programming space. Plans were made to bring it back in 2020 – but the COVID-19 pandemic put those plans on hold. As theatres reopened, it became clear that CFT’s future needed to respond to a changing world, evolving audience behaviours, and the wider needs of the creative community. It was time to imagine a new kind of space – and so began planning for the next chapter...

2025

Introducing The Nest

Chichester’s new creative space for fresh ideas, new voices and local artists. The Nest is part of CFT but with a more intimate, informal vibe. Think fringe theatre, open mics, live music, interactive shows for early years, and community-led events – all in one welcoming space. Come see something different or start something yourself. Whether you’re watching, performing or producing, The Nest is a place where stories are shared, experiments take shape and ideas come to life. From September 2025, Thursday to Saturday, The Nest will be home to live events you won’t find anywhere else in Chichester – from up-and-coming comedians and acoustic gigs to new theatre and interactive shows for little ones. All tickets are under £20, and it’s always unreserved bench seating. Just turn up, grab a drink, and dive in.

Legacy & Impact

Building platforms,not just spaces

Over five decades, Chichester Festival Theatre has quietly carved out a powerful legacy – not through grand declarations, but by building platforms. The Tent, Theatre on the Fly, the

Spiegeltent, and now The Nest, were never just architectural experiments. They were – and are – launch pads: creative habitats for emerging artists to take flight, connect with others, and discover their own voice. This exhibition shared just a fraction of that story. What emerged clearly is a sustained commitment to nurturing the next generation. CFT didn’t replicate what others had done – it created something distinct. Something lasting.

A theatre built by the community, for the community.

Between 1980 and 1983, Chichester Festival Theatre’s use of pop-up spaces reflected a growing national interest in temporary theatre venues. The Tent was ahead of its time, offering young artists a platform and attracting new, younger audiences. Unlike some theatres that relied heavily on government funding, CFT’s temporary spaces were rooted in community support, with a focus on accessibility and creativity over profit. What sets CFT apart is its deep grounding in the community: a regional theatre that has consistently made space for ambition, risk, and radical creativity. That includes not just new artists but local people – from workshop participants to wardrobe volunteers – who shape and support every stage of the journey. Temporary spaces like The Tent and The Nest are reminders that great theatre doesn’t just come from bricks and mortar, but from a network of people, passion, and purpose.

'While many pop-up venues symbolised financial necessity or artistic rebellion, CFT’s spaces stood out for combining community ethos with innovation – quietly shaping the trend rather than following it.'

Chichester art and legacy

Chichester’s vibrant arts scene blossomed from the 1975 Chichester Festivities, originally a one-off celebration for the Cathedral’s 900th anniversary. So beloved was the event that it became an annual highlight, evolving into today’s renowned Festival of Chichester. The city’s commitment to the arts is deeply intertwined with Chichester Cathedral, where visionary patrons like Dean Walter Hussey championed modern art – most famously commissioning Marc Chagall’s stunning stained-glass window, The Arts to the Glory of God. Meanwhile, Pallant House, an 18th-century Georgian gem, transformed into a leading modern art gallery thanks to passionate local advocates. Theatre thrived too, ever since the founding of the Chichester Festival Theatre in 1962, envisioned as a self-sustaining cultural beacon. From amateur operatics to groundbreaking festivals, Chichester has grown into a vital creative hub, blending heritage and innovation at the heart of its artistic identity.

We have to find ways to create launch pads for young talent to move forward

Alice O’Hanlon, Artist Development Programme